Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a set of substances that have been used since the 1940s in various industrial applications like paper making, textile mills, electroplating, firefighting foams and in consumer products like non-stick cookware, stain repellent clothing, food contact materials, paints, cosmetics, detergents and other cleaning products. The term ‘PFAS’ is accepted as the overarching term for the entire class of these synthetic compounds. There are more than 9000 known PFAS compounds, but the global regulation list covers less than 50 compounds. Out of these many PFAS compounds, the most widely used compounds in early industrial applications were…

• PFOA: Perfluoro octanoic acid, which has an eight-carbon chain length with a carboxylic acid functional group at one end, and

• PFOS: Perfluoro octane sulfonic acid, which has eight carbons in an alkyl chain with a sulfonic acid end group.

Therefore, PFOA and PFOS are the first two compounds widely studied in the PFAS compound class.

Occurrence & toxic

The ubiquitous presence of PFAS in industrial waste waters is attributed to PFAS-producing or -using industrial sites. However, their presence in municipal waste waters, such as in septic tanks and office buildings, is suspected either due to environmental degradation of polyfluorinated microfibers released by stain-resistant clothing during laundry, or human excretion after oral exposure. Often, a portion of the PFAS in wastewater effluent can be ascribed to PFAS in the community’s tap water. PFAS detected in wastewater and biosolids include not only the two most studied chain PFAS and polyfluorinated compounds. PFAS, perfluoro octane sulfonic acid (PFOS) and perfluoro octanoic acid (PFOA), but also short-chain PFAS and polyfluorinated compounds.

The industrial utility of PFAS compounds is due to their strong carbon-fluorine bond, and as a result these PFAS compounds were thought to be very inert and stable. Unfortunately, that also means that they do not break down in the environment and can stick around for decades. Therefore, PFAS have become pervasive and present throughout ecosystems and our daily lives.

The significance of knowledge about PFAS’s presence and quantitation lies in their persistence, bioaccumulation, and toxicity. PFOA has probable links with several toxicological end points, including kidney cancer, testicular cancer, and high cholesterol. PFOS has been linked with reproductive toxicity, immune effects, and kidney toxicity in laboratory animals. Biomarker studies have indicated similar effects in humans. Therefore, PFOA and PFOS have been phased out in the countries like United States and replaced by short-chain PFAS, polyfluorinated compounds, and perfluoro ethers. These shorter-chain alternatives have shorter half-lives in the human body. Less is known about the toxicity of short-chain PFAS, but precaution is warranted on the basis of the similarity of their persistence to that of PFOA and PFOS.

Human exposure

Since PFAS have been widely used for decades and do not easily break down, these compounds have been detected in almost every ecosystem that interacts with humans, such as drinking water, wastewater, soils, food, and air. PFAS are poorly removed by Waste Water Treatment and conventional Drinking Water treatment plants. Without appropriate mitigation methods, human exposure could occur from wastewater through various means:

• Treated water discharge – Once wastewater is treated, it is discharged into the local environment. If this treated effluent contains PFAS, it then contaminates its receiving water that may be a source water for a downstream public water supply.

• Waste water reuse – In certain cases, the waste water is comprehensively treated to the standards of potable water. Intended use of treated waste water could expose humans and animals to PFAS.

• Biosolids – Wastewater treatment processes also produce a significant amount of sludge, often referred to as biosolids when applied as fertilizer. This application potentially introduces PFAS into the food chain through plant uptake as they are bio accumulative.

• Leaching – When biosolids of waste water treatment plant are not used as fertilizers, the alternative is to send them to a landfill site, from where PFAS compounds can leach into the ground water.

Treatment of PFAs

Removal of PFAS from effluents prior to discharge is an important downstream strategy for preventing continued emissions. As a matter of fact, PFAS are mostly not removed with conventional primary and secondary treatment steps for wastewater, although some adsorption to sludge may occur.

Existing wastewater treatment technologies that are effective for the removal of PFAS from water are very few, which mainly include thermal destruction, ion exchange, membrane filtration and adsorption. But these technologies are energetically and financially costly, particularly for complex matrices. Extensive pretreatment is often required.

Thermal destruction by incineration

Incineration is a well-known and energy intensive mineralization pathway for the removal of harmful compounds using heat, where high temperatures I ranging from 600°C to 1000°C are applied to destroy PFAS. Though this is an established process for treatment, there are possibilities of release of gaseous toxic substances like furan and dioxins into the environment while dealing with degradation of certain PFAS compounds. In such cases, a polishing step with air filters is necessary to remove the vaporized contaminants.

Thermal destruction by Pyrolysis / Gasification

Both these processes decompose materials at elevated temperatures, but decomposition by Pyrolysis is in an oxygen-free environment, whereas Gasification uses small quantities of oxygen. The oxygen-free environment in pyrolysis and the low oxygen environment of gasification distinguishes these techniques from incineration. Pyrolysis, and certain forms of gasification, can transform input materials, like biosolids, into a biochar while generating a hydrogen-rich synthetic gas (syngas). These processes potentially destroy PFAS by breaking apart the chemicals into inert or less recalcitrant constituents. However, this mechanism, as well as evaluation of potential products of incomplete destruction, remain a subject for further investigation and research.

Ion exchange

Anion exchange resins have been utilized as treatment methods for separating PFAS from liquid streams, often at a fraction of the cost of other separation technologies such as nanofiltration and reverse osmosis. It is commonly used during groundwater site remediation and drinking water treatment. This treatment involves ion exchange onto a positively-charged surface. The surfaces of the resins become saturated over time and no longer able to remove PFAS. These resins may or may not be amenable to regeneration. Spent resins are either landfilled or incinerated. The former may lead to PFAS ending up in the landfill leachate.

Granular activated carbon (GAC)

Granular activated carbon (GAC) is generally used to separate PFAS during manufacturing as well as drinking water treatment. It removes PFAS compounds from liquid by surface adsorption. The surface become saturated over time and no longer able to remove PFAS. GAC can be regenerated but eventually loses its effectiveness and must be disposed. Spent GAC is either disposed by landfilling or incineration. Landfill disposal may again lead to PFAS leaching in ground waters.

High-pressure membranes (nanofiltration /RO)

These types of membranes are typically more than 90 percent effective at removing a wide range of PFAS, including shorter chain PFAS. RO membranes are tighter than nanofiltration membranes. Therefore, while nanofiltration membrane will reject hardness to a high degree, but pass sodium chloride; the reverse osmosis membrane will reject all salts to a high degree. This difference allows nanofiltration to remove particles while retaining minerals that reverse osmosis would likely remove. Approximately 20 percent of high-strength concentrated waste is difficult to treat or dispose. Like in other treatments, the concentrated waste needs to be treated through thermal degradation.

Emerging treatment technologies

The efficiency and practicality of the treatment technologies for per-fluoroalkyl and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) removal are not cost-competitive sometimes. Also, successful removal of PFAS has been to a limited level in aqueous streams only. Further, the biological approaches to treat PFASs are extremely limited and are not currently considered as viable. Nevertheless, the treatment technologies are still evolving and they are considered as I effective approaches for PFAS removal and have shown promising results for long chain and some short chain PFAS compounds. However, much work on application of these technologies on large scale commercial treatment facilities is not done.

Electro chemical oxidation

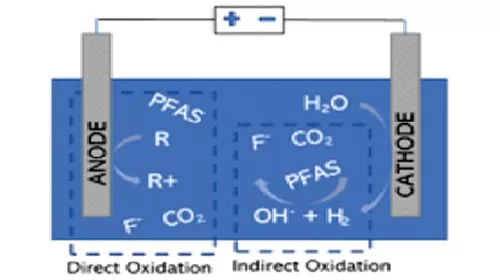

This technology uses electrical currents passed through a solution to oxidize persistent organic pollutants, such as PFAS. As shown in Figure, both direct and indirect oxidation mechanisms are possible. Direct oxidation can result by electron transfer from the PFAS compound to the anode, while indirect mechanisms involve electrochemically created, powerful oxidants known as radicals (such as hydroxyl radical, OH).

This is a promising technology in view of low operating costs, operation at ambient conditions, ability to be in a mobile unit, and no requirement of chemical oxidants. However, much work on commercialization of this technology is not done. Various other factors like disposal of generated toxic byproducts, incomplete destruction of some PFAS, efficiency losses due to mineral build up on the anode, and high cost of the metal electrodes also need attention before adoption.

Mechanochemical degradation

In this technology, the destruction of PFAS is undertaken in a high-energy ball-milling device. The technique does not require solvents or high temperatures to remediate solids and therefore can be considered a “greener” method of treatment. Agents like silica, potassium hydroxide, or calcium oxide are added as co-milling agents to help react with fluorine and to produce highly reactive conditions. The crystalline structures of the co-milling reagents are crushed and sheared by high energy impacts from stainless-steel milling balls in the rotating vessel.

This method performs best with dry, sandy soil. The effects of various matrices, the effectiveness of different co-milling reagents, the possibility of loss of volatile PFAS, performance efficiencies etc should be studied before this technology is applied at large scale.

Supercritical water oxidation

Water above a temperature of 705 °F and pressure of 221.1 bar is considered “supercritical”, a special state of water where certain chemical oxidation processes are accelerated. This technique has been used successfully to treat various halogenated waste materials containing fluorine, chlorine, bromine, or iodine for many years. Organic compounds, usually insoluble in water, are highly soluble in supercritical water. In the presence of an oxidizing agent (such as oxygen), supercritical water dissolves and oxidizes various hazardous organic pollutants.

This technique has a potential for PFAS destruction by breaking the strong carbon-fluorine bonds decomposing them into a non-toxic waste stream. Along with potential, this technology also presents several technical challenges like buildup of corrosive gases during the oxidation reaction, precipitation of salts, and high energy requirements.

Photodegradation by UV light (photolysis)

Continued exposure of PFAS to radiation with wavelengths less than 320 nm, known as actinic wavelengths, results in photodissociation via photolysis, in which, the dissociation of organic pollutants is motivated by the adsorption of photons, thus providing a new reaction pathway via the formation of electronically excited reactive species.

Two forms of photolysis are capable of degrading PFAS: (1) Direct photolysis and (2) Indirect photolysis. In direct photolysis of PFAS, photons are directly absorbed by the PFAS, causing it to undergo photodegradation. For indirect photolysis, separate compounds like UV/H2O2, UV/Ozone, and photo-Fenton absorb photons and then work as an intermediate to react with PFAS. In this regard, for a practicable photolysis process, the strong C-F bond in PFAS is cleaved by UV irradiation into fluoride (F-) ions.

Photocatalytic degradation

Photocatalysts present in water under UV light irradiation produce reactive species such as hydroxyl radicals as well as other photochemically generated reactive intermediates.

These reactive species actively react with pollutants such as PFAS to degrade them into harmless intermediates.

Sonochemical / Ultrasound degradation

Sonochemistry involves the use of acoustic field to generate radicals to degrade contaminants in various aqueous media. More specifically, ultrasonic irradiation causes acoustic cavitation (i.e. bubbles collapsing in solution due to sound waves), which creates high temperature and pressure conditions resulting in the pyrolytic degradation of PFAS at the bubble-water phase. In these bubbles, the average internal vapor temperature increases to 4000 K, while bubble-water interface temperatures are generally in range from 600 K to 1000 K. These momentary high temperatures assist in the in-situ pyrolysis of water into hydrogen and oxygen atoms as well as hydroxyl radicals in the interfacial and vapor regions of each collapsing bubble. The resulting radicals react quickly with organic molecules at the bubble interface or in the bubble interior gas-phase. PFAS compounds are decomposed at the interfacial area between the bulk solution and the cavitation bubbles.

This technique is found highly effective at bench scale. However, PFAS treatment under sonication at a large scale has not been studied much. Optimization of frequency and power is also required to be addressed while considering PFAS mineralization via sonication.

Advanced oxidation / Reduction processes

Highly reactive oxidant species (ROS) such as hydroxyl and sulfate radicals are employed in advanced oxidation process to destroy C-F bonds and separate the head groups, in addition to scissoring the CC chains. In advanced reductive process, UV / sulfite are employed in which the hydrated electrons cleave the resistant C-F bonds.

Since the toxicity and stability of PFAS are more likely attributed to the fluorine atoms, scissoring of carbon skeleton without cleavage of C-F bonds induces shorter chain PFAS that still possess toxic and persistent nature. Notwithstanding the numerous studies reporting the successful defluorination and degradation of various PFAS, the degradation pathways and mechanisms are not fully understood.

Plasma technology

Plasma is a moderately or entirely ionized gas formed by electrical discharge. It contains free neutrons, electrons, free radicals, ions, and atoms in heightened energy states. In terms of temperature and electron density, plasma systems can be characterized into two groups: nonthermal plasma process and thermal plasma process.

Generation of thermal plasma through torches or radiofrequency arc discharge is characterized by increased energy and plasma elements in thermal equilibrium. High energy ions in plasma continuously degrade the carbon chains of PFAS. Non-equilibrium or non-thermal plasma is based on the production of highly reactive atomic hydrogen and oxygen, hydroxyl and hydroperoxyl radical, nitrogen-species, aqueous electrons etc. Since nonthermal plasma contains such a rich and reactive chemistry, it presents promise for its use for removal of very recalcitrant compounds.

Conclusion

Remediation of Poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in the environment has rapidly increased due to growing concerns of environmental contamination and associated adverse toxicological effects on wildlife and humans due to bioaccumulation and extreme persistence. Although, PFAS are highly recalcitrant to conventional waste water treatment processes, there are some effective techniques available. But they involve exceedingly high energy costs, capital or operational costs. Most of the separation and destruction techniques have their own limitations in field applications. They demonstrate capability of removing long-chain PFAS. During treatment, the PFAS might degrade into short-chain PFAS, which might be more stable in the environment. The degradation can also result in the generation of novel PFAS which are not well-established and may have negative consequences for the environment, human beings or animals. Therefore, the treatment method is required to be chosen on the basis of initial concentration of PFAS and the treatment objectives.

The biological approaches to treat PFAS are extremely limited and are not currently considered as viable. Various novel and advanced techniques for treatment of wide array of PFAS compounds are found promising and effective on laboratory or bench scale. Therefore, it is essential to understand the removal mechanisms to optimise the advanced treatment processes. Careful selection of a combined, hybrid and effective treatment methodology in an integrated processing unit would be an ideal approach for treatment of PFAS in the wastes.